This work examines how inherited sonic and visual archives can become active sites of artistic knowledge production through research-creation practice, specifically investigating questions of cultural transmission, embodied interpretation, and technological mediation in reactivating dormant cultural materials.

Origins of the Project:

Ethereal Channels of Existence is rooted in over a decade of creative inquiry, originating in 2010 with the launch of my project Syngja. The name, derived from the Icelandic verb að syngja (“to sing”), emerged from repeated listening to cassette recordings of my great-grandmother, Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir (1891–1994) (Figure 1), who began each song with the phrase Ég ætla að syngja… (“I'm going to sing”). Born in Iceland and having immigrated to Selkirk, Manitoba in 1925, Ingibjörg recorded Icelandic poetry, folk songs, and personal reflections onto cassette tapes in her eighties and nineties, creating intimate audio letters for her daughter, Jóna, and for future generations (Figure 2). These recordings form a vital intergenerational archive that preserves cultural memory and familial intimacy.

These recordings served as the foundation for early experiments integrating improvised cello and cassette loop performances, which are featured on my 2012 album Bow and Arrow. Intricately weaving ancestral resonance with contemporary artistic methodologies, this debut album, described by author Lisa Sproull at Cult MTL as “lush, melodic and dramatic, folding together elements of Icelandic folk music, classical string arrangements, and pop structuring,”[2]represented a pivotal moment in the project's evolution. This foundation culminated in the 2016 album Lang Amma, named after the Icelandic term for great-grandmother, and in audiovisual performances titled New Spring (2015-2017), supported by the CAC Research-Creation InterArts Grant.

[2] Lisa Sproull, “Syngia’s New Record Is Interwoven with Their Icelandic Folk Roots,” Cult MTL, May 17, 2016, cultmtl.com/2016/05/montreal-band-syngia/.

The act of engaging creatively with historical cultural artifacts (cassette recordings, film) addresses how they can be transformed into dynamic resources, while engaging with what folkloristics scholar Terry Gunnell calls the need to resurrect 'the valuable missing context surrounding ancient oral remains' through contemporary lived experience.

Improvisation and ancestral voice

Much like the sculptural process described by author and composer Dane Rudhyar, where “the hands of the sculptor are allowed gradually to release from the chunk of matter a form which the sculptor comes to realize has been held in latency by the stone.”[1] The folksongs function as foundational material possessing latent potential, progressively revealed through engagement with their intrinsic essence. This aligns with the experimental approach of Musica Elettronica Viva, an avant-garde musical collective from the late 1960s. This methodology is grounded in a phenomenological understanding of embodied experience and guided by the four-stage framework articulated by american composer and performer Larry Austin, who describes a process of intuitive creation shaped by openness and identification with the material:

1. First, the mind goes blank. It is all about relaxation, emptiness, and freeing oneself from conscious control.

2. Next, one opens the mind to free-floating images. In other words, free association. By fixing the mind upon an image of anything, it becomes concrete, both spatially and temporally.

3. Then comes the moment of locking into the image: identifying with it, becoming it. As Austin writes, “the soul of the thing that speaks through them.”

4. Finally, everything with a soul must die. “Should I become this thing, I will die with it.”[2]

Through identificatory fusion with the folksong, allowing myself to be transported and transformed by it, the original dissolves, giving birth to new musical expressions. This mirrors what composer Meredith Monk describes as starting “from zero in every piece, not to think about it in terms of product or what my piece should be like or doing what I've done before, but going to the edge of the cliff each time. […] to follow and to delineate a mystery.” [3]

[1] Dane Rudhyar, “The Spatialization of the Tone-Experience,” in The Magic of Tone and the Art of Music (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 1982), 134.

[2] Larry Austin et al., “Musica Elettronica Viva Words,” in Source: Music of the Avant Garde, 1966–1973 (University of California Press, 2011), 106.

[3] Ibid.

Les 9 Mondes (Movement I)

Les 9 Mondes features two pieces: Abundance, and Nouvelles Roses, inspired by the Icelandic poem Þrek og tár.

Abundance

The first section (00:00-01:39), linked to Ásgarður and human aspiration, resonates with Álfheimur, the realm of the Light Elves in Yggdrasil— “a magical place of light and hope, visions and ambition.”[1] It evokes the moment of departure. This journey is articulated through lyrics that channel this sense of inner awakening and the flow of emergent energy:

Lyrics:

Embark on a path, that brings abundance

Ever-flowing harmony

Effortless mastery, notes between notes, rolling through the body

You broke your chance you went so silent, it wouldn’t have grown back, breaking the truce

They make mistakes over, they must be seen in the wilderness

That’s the most you can do,

Drowning with indecision, drowning with all your might, going up to you

My vulnerabilities’ your bait, the bait you use to capture me with

[1] Haukur Halldórsson and Gunnhildur Hauksdóttir, “Alfheim: The World of the Light Elves,” in Yggdrasil: Norse Divination Cards (Llewellyn Publications, 2019), 63.

Figure 3. Screenshot from Abundance - section A © 2024 Tyr Jami.

Nouvelles Roses

Nouvelles Roses weaves together elements of oral tradition, synchronistic composition methods, inherited folk material recontextualization and landscape visuals. It delves into themes of past lives and rekindled connections.

In my work Nouvelles Roses, I incorporate the sounds of cassette player clicks when Ingibjörg's voice emerges, thereby creating textural transitions between different sonic worlds. This technique mirrors Twigs' approach in her 2022 release CapriSongs, where she intentionally includes cassette player clicks to evoke the intimate and spontaneous feeling characteristic of a personal mixtape. As critic Cat Zhang remarks regarding Twigs' work:

Caprisongs is the sound of twigs in the driver’s seat as she traverses her own curiosities and instincts; there is no man looming over the music, no weighty public narrative dictating its terrain. It is intrepid and light, the image of a woman attuned to planetary alignments but casting her own fate.[1]

[1] Cat Zhang, “FKA Twigs: CAPRISONGS Album Review,” Pitchfork, January 17, 2022, pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/fka-twigs-caprisongs/.

Figure 5. Screenshot from Nouvelles Roses © 2024 Tyr Jami.

Figure 6. Translated text of inherited cassette tapes © 2024 Tyr Jami.

Ingibjörg's sampled voice provides gentle narration throughout Nouvelles Roses, with her reflective commentary at 3:18: You have to read into it, you have to sing the poem […] I have nothing written down. The composition demonstrates synchronistic alignment of original lyrics with inherited poem content. Parallels emerge between the original lyrics and the Icelandic poem. Push your feet on the ground speaks of strength and grounding, which paralells Why cry over old dreams, unreal fantasy? Let your strength take over the wheel. Similarly, You Couldn’t See That Way resonates with It’s good that you don’t understand my tears. You neither know nor understand the matters of the heart. (see Figures 6 and 7), This demonstrates how traditional material can be animated through contemporary interpretation while maintaining essential character. The work employs processing techniques that preserve the integrity of Ingibjörg's vocal performance while integrating it into contemporary compositional structures.

The song samples the Icelandic poem Þrek og tár by Guðmundur Guðmundsson, performed by Ingibjörg in 1977. The poem and the original lyrics carry a quiet sadness, a longing, and the unspoken pain of matters of the heart.

Original lyrics:

Send your love this way, count the stars on your face

Press your face onto mine, once you’re free of me, send your love this way

You’re safe put your head on me, but you’re safe put your head on me

You couldn’t see that way

Press your face onto mine, push your feet on the ground, once your free of me…

Figure 7. Translated text of inherited cassette tapes © Tyr Jami 2024.

La Fôret Invisible (Movement 2)

La Forêt Invisible shifts toward the hidden and seen worlds through portal-like transformations.

La Forêt Invisible examines the themes of mystery and invisibility conveyed in the Icelandic folksong Amma Raular í Rökkrinu. The line 'No one knows where the wishing stone lives' signifies a pursuit to find something hidden, while personifying the stone as an entity with a habitat, suggesting they are nátturuvættir (nature spirits)[1]. You can easily see faces and forms of beings within the stones (see below), suggesting that the population of nátturuvættir may exceed that of ordinary humans. The study of the folksong and the compositional process are intrinsically interconnected, as visuals depict Icelandic stones believed to house spirits, as well as dancers who embody and represent the shape-shifting Norse god Loki.

[1] Terry Gunnell, “The Álfar, the Clerics and the Enlightenment: Conceptions of the Supernatural in the Age of Reason in Iceland,” 192.

Originally conceived as a continuous 10-15 minute audiovisual composition (as seen in the video below), La Forêt Invisible has been organized into four sections for analytical purposes: Moment, Wait for the Sun, New Found Stillness, and Twin Peaks.

Moment

In Iceland's cultural geography, mythological narratives are intrinsically connected to the physical landscape. The landvættir (land spirits) and nátturuvættir (nature spirits)[1] live within sacred topographies, inhabiting the hills, rocks, mountains, caves, groves, trees, and waterfalls[2] that punctuate the landscape.

[1] Terry Gunnell, “The Álfar, the Clerics and the Enlightenment: Conceptions of the Supernatural in the Age of Reason in Iceland,” in Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits, ed. Michael Ostling (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 192.

[2] Thomas A. DuBois, Nordic Religions in the Viking Age (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 50.

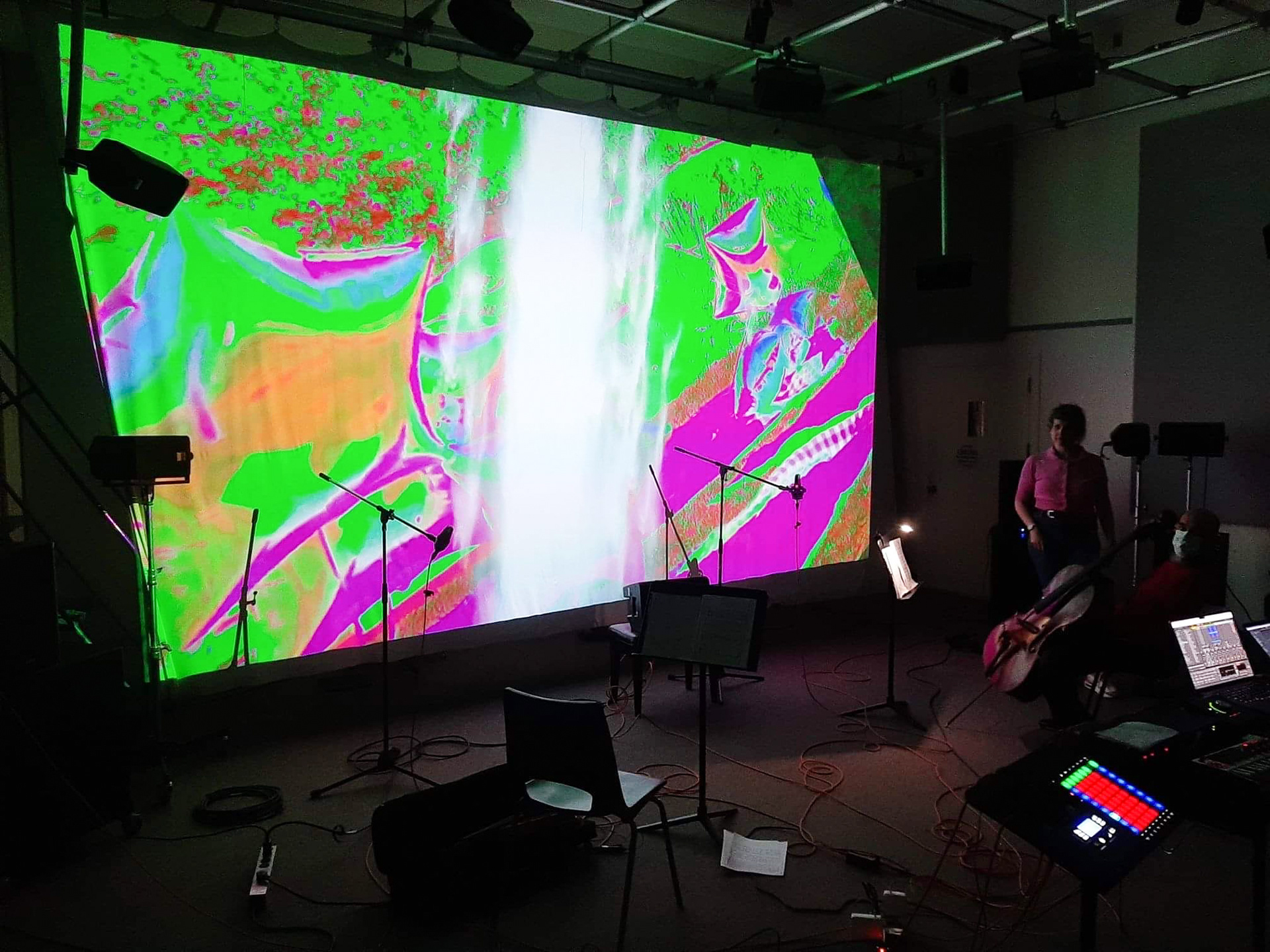

Moment (0:00-4:32) explores stone symbolism implementation, audio-reactive portal effects, and MIDI folk song manipulation. The piece opens with a ten-second segment sampled from Icelandic folk melody rendered into a MIDI instrument, followed by lyrics the calm that we wished for... The compositional visual treatment involves layering magenta tones and generating mirrored, audio-reactive effects to Reynisfjara's basalt formations into portal-like imagery (Figure 9).

The string arrangement thickens the melody by having the strings play in octaves[1]. The dual voice lyrics—Forgot to take off your shoes, may you not believe the truth…How should you feel... and What would you expect?—are emphasized by the audio-reactive mirror effect mapped to the kick drum.

[1] See the scores of Moment in Annex 2.

Figure 9. Screenshot from Moment © 2024 Tyr Jami.

As Professor of Folkloristic, Terry Gunnell states, “Supernatural beings […] were believed to inhabit the natural environment of Iceland,”[1] and “[…]sitting by a waterfall, seems to have had the potential of giving you access to the knowledge and skills of the other side’, which you could not gain elsewhere.” [2] As Social Anthropologist Adriënne Heijnen explains, “[being] similar to humans, the distinction between huldufólk and humans is essentially rooted in a distinction between invisibility and visibility.” [3] We will see in Chapter 3 how these ideas are implemented through imagery of stones and waterfalls, which function as symbolic motifs, evoking geological formations as metaphysical interfaces, and the shapeless adaptability of water as a symbol for the transformative process itself. The water symbolism extends throughout the compositional process, where fluid, evolving improvisations reflect water's capacity for metamorphosis while maintaining essential qualities.

This perspective reflects the traditional Icelandic understanding of place as a carrier of myth and memory, and what Gunnell describes as “mystical knowledge and power that was seen as being related to the world of the dead.”[4] In this view, geographical locations serve as dynamic repositories of cultural knowledge. As Gunnell further explains, “cites where worlds met and lives were transformed. They were portals of a kind in which one could communicate with the other world, and in which the other world had access to ours, and could wield influence.”[5] With live performance serving as an integral element of the compositional process of Ethereal Channels of Existence, I position myself at the periphery, engaging in communicative acts, where the mystical nature elements of a waterfall or elf church are depicted through visual representations.

[1] Terry Gunnell, “The Álfar, the Clerics and the Enlightenment: Conceptions of the Supernatural in the Age of Reason in Iceland,” 192.

[2] Terry Gunnell, “Spaces, Places, and Liminality: Marking Out and Meeting the Dead and the Supernatural in Old Nordic Landscapes,” in Landscape and Myth in North-Western Europe, ed. Matthias Egeler (Brepols, 2019), 37.

[3] Adriënne Heijnen, “Dreams, Darkness and Hidden Spheres: Exploring the Anthropology of the Night in Icelandic Society,” Paideuma 51 (2005): 199, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40341894.

[4] Terry Gunnell, “Spaces, Places, and Liminality: Marking Out and Meeting the Dead and the Supernatural in Old Nordic Landscapes,” 33.

[5] Ibid.

Wait for the Sun

Figure 10. Screenshot from Wait for the Sun © 2024 Tyr Jami.

Through audio-reactive visuals and flickering mirror effects of a live dance battle, Wait for the Sun explores lyrical components inspired by the Norse myth of the Sun. This creates an interplay between sound and visual elements through embodied performance, where dancers symbolize the shapeshifters or Huldufólk: the hidden people of Icelandic folklore, often described as invisible beings who live in nature (such as within stones) and possess the ability to change form. The dancers in the visuals embody the norse god Loki, “the court jester among the gods,”[1] reflected through playful, mischievous movements, complemented by audio-reactive effects linked to vocal processing and color shifts (Figure 10). The themes of visibility and invisibility described in Chapter 1 are implemented both lyrically and visually through audio-reactive effects applied to the on dancers' footage.

[1] Paul Acker and Carolyne Larrington, eds., The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology (Taylor & Francis Group, 2002), 237, ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/umontreal-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4218242.

New Found Stillness

New Found Stillness focuses on the integration of lightning symbolism and the processing of 8mm footage. It relates to the element of air, whispers, clouds and secrets.

Original Lyrics:

New found stillness, whispers of hope. Winding roads, rituals, breathing truth

I don’t know what to tell you, you seem to be so sure

(instrumental break)

The lights are flickering, the battery is low

Clarity follows thunder, the strongest kind

The accompanying 8mm imagery of an eagle (See Figure 11) symbolizes sky, tranquillity, and clarity. These visual motifs are enhanced with audio-visual effects that build tension and release, using dynamic processing techniques to mirror the emotional arc of the piece.

Figure 11. Screenshot from New Found Stillness © 2023 Tyr Jami.

Figure 8. Screenshot from La Forêt Invisible (8mm inherited film of a stone) © 2023 Tyr Jami.

Twin Peaks

The visuals of Twin Peaks give the impression that we are in a dark, magical, yet scary forest. The path, symbolizing identity, gets swept away by a broomdog, the video on loop goes in continual cycles, so when she thinks she finds the path, she goes around in circles and never actually finds her way out. In the dark unknowns of life, we can sometimes get glimpses of clarity. But like the story of Alice in Wonderland, any sense of seeming stability in our lives could be swept away at any moment.

Also related to Iceland’s Huldufólk, or hidden people and shapeshifters, Twin Peaks engages with themes of shadow confrontation, dimensional projection concepts, and unknowability as a compositional element. Its instrumental theme is accompanied by audio-reactive effects that create a mirror image of Alice in Wonderland, embodying the expression of the subconscious, flickering in and out with the vocal effects (below).

The lyrics are from the perspective of the protagonist, Alice:

Ask yourself, your sense of smell

Sense of your humanness

Yr sense of yourself, sense of decay

Can’t you see, can’t you breathe, nobodies perfect

Nobody knows what you see, it’s yr favourite place to be, it’s your sense of yourself

Can’t afford the competition, nobody's listening, yr invisible, its an illusion, nothing is real, nothing can hide, you own yourself.

Figure 12. Screenshot from Twin Peaks © 2024 Tyr Jami.

Sleep Darling (Movement 3)

Sleep Darling implements string arrangements through mythological narratives, water symbolism and environmental visual integration.

The third and last movement, Sleep Darling, explores a compositional process grounded in the transformation of an Icelandic lullaby into three distinct pieces: The Hike, The Sacrifice, and Water Creature. Sessions of inspiration and research were carried out at the mythological Dynjandi and Skógafoss waterfalls (Figure 13 and Figure 14), whose symbolic resonance and sensory presence informed the overall atmosphere of the movement.

Imagery of stones and waterfalls function as symbolic motifs, evoking geological formations as metaphysical interfaces, and the shapeless adaptability of water as a symbol for the transformative process itself. The water symbolism extends throughout the compositional process, where fluid, evolving improvisations reflect water's capacity for metamorphosis while maintaining essential qualities.

This perspective reflects the traditional Icelandic understanding of place as a carrier of myth and memory, and what Gunnell describes as “mystical knowledge and power that was seen as being related to the world of the dead.”[1] In this view, geographical locations serve as dynamic repositories of cultural knowledge. As Gunnell further explains, “cites where worlds met and lives were transformed. They were portals of a kind in which one could communicate with the other world, and in which the other world had access to ours, and could wield influence.”[2] With live performance serving as an integral element of the compositional process of Ethereal Channels of Existence, I position myself at the periphery, engaging in communicative acts, where the mystical nature elements of a waterfall or elf church are depicted through visual representations.

Figure 16. Screenshot from The Hike (liquid) © 2021 Tyr Jami.

I composed Sleep Darling during the Musique Mixte class with Pierre Michaud (2022/2023) at Université de Montréal. This context involved recording, sampling, and improvisational techniques with classical musicians. The recordings of several Icelandic folk songs with two cellos, performed by Jefferson Perez and myself, and Alban Cellier on violin, provided melodic and rhythmic sound banks to draw from.

Sofðu Unga Ástin Mín (see Figure 15), composed by Jóhann Sigurjónsson (1880-1919), was chosen to intertwine the timeless essence of folk tradition with a contemporary creative process.

Icelandic lullabies, were historically sung to infants being “cast out.” The essence of Sleep Darling thus delineates a narrative of symbolic sacrifice and transformation, rooted in the themes of melancholy and haunting beauty inherent in the traditional folk song, through improvisational techniques and the recontextualization of folkloric footage.

Combined with my travels in Iceland, each Icelandic folk song and location became a narrative that inspired this work, enabling new interpretations of folk songs and tales. For example, the Dynjandi waterfall (Figure 13), also known as “The Thunderer,” is steeped in legend, with one tale describing a supernatural being that inhabits the falls and another claiming that the waterfall is the bridal veil of a giantess abandoned in grief, with its thunderous sounds embodying her sorrow.

Figure 15. Sample modes (left © Tyr Jami) and Sofðu Unga Ástin Mín (right © Public Domain).

Original footage of Icelandic nature is integrated through Resolume’s audio-reactive visual effects in real time. This demonstrates the application of three water states through original footage of Icelandic nature informing the visual elements: liquid, (The Hike, Figure 16), vapour (The Sacrifice, Figure 17), and solid (Water Creature, Figure 18).

The Hike (Once in a Lifetime)

The Hike represents the stage in the hero's journey where doubts arise about the path taken, encountering the first obstacle that must be overcome.

Intuition and Transformation

Intuition propels ideas that often lead to transformative outcomes. As anthropologist Adriënne Heijnen observes,“[darkness] in Iceland is conceptually associated with parts of the world that are hidden from the waking mind, while light is linked to the living human world. Dreaming is ascribed the ability to render the hidden parts of the world transparent.”[1] This connection between inner states and access to hidden dimensions finds resonance in the realm of artistic intuition.

Composer Pauline Oliveros, in Deep Listening, reflects on intuition as a mode of perception that bypasses rational control: “[intuition] is direct knowing. Intuitive messages come to us as flights of imagination or in dreams. Intuition is associated with the future. We can project ourselves into the future through our intuition.”[2]

The Sacrifice (Mine)

The Sacrifice utilized one of the overarching methodologies for this research-creation project, which draws on what Icelandic traditions call Magic Writing, an alchemical approach that combines seemingly unrelated elements to create new forms of meaning and expression.

Figure 17. Screenshot from The Sacrifice (vapour) © 2022 Tyr Jami.

As described by Icelandic writer Oddný Eir:

[...] in old Icelandic, was called magic writing, that you would put two different things together and that would, uh, open something…You cannot understand it in a logical way, somehow, why this element and this element together, is like this alchemical process. […] the synergy of it will become something totally else, […] a key to..to a whole dimension. And what I'm describing is actually the quality of mystical writings.[1]

The juxtaposition of temporal, cultural, and sonic materials generate unexpected connections and revelations through automatic writing, singing and improvisation. This is a process of making work that composer and singer Meredith Monk describes as “[…] that idea of letting go of intention so much that whatever work is going to be made literally comes through you. It has to do with not knowing what the result is going to be.”[2] Analogous to the approach employed by cellist, singer, and composer Gyða Valtysdottir, who states, “I had felt a strong presence of a spirit who wanted to be embodied through me, he somehow co-created this song with me, I felt I only had to listen and follow.”[3]

[1] Oddný Eir, “Debut - Sonic Symbolism,” Mailchimp Presents, www.mailchimp.com/ presents/podcast/sonic-

symbolism/, accessed May 5, 2025.

[2] Bonnie Marranca, “Art as Spiritual Practice: A Conversation with Meredith Monk, Alison Knowles, Eleanor Heartway, Linda Montano, Erik Ehn,” in Performance Histories (New York: PAJ Publications, 2008), 173.

[3]Tobias Fischer, “15 Questions | Interview | Gyda Valtysdottir | Co-Creating Spirit.” 15 Questions, www.15questions.net/interview/fifteen-questions-interview-gyda-valtysdottir/ page-1/, accessed August 14, 2024.

Original Lyrics:

Do you need to be here, would you stay still

Would you be on time, would you still be here

Would you stay for sure, would you be mine

Would you be still here, would you be mine

could you stay still would you be mine

Stay still could you be friends with me

Could you be, could you be.

Water Creature

Sleep Darling culminates in a surprising twist: in the traditional tale, the newborn baby is thrown to its death, but in this reimagined version, the child encounters the Lagarfljót Worm, a mythical sea creature (see Figure 19), suggesting that what was once perceived as a sacrifice transforms into a meeting with a new, fantastical reality.

Figure 18. Screenshot from Water Creatures (solid) © 2024 Tyr Jami.

This research on sea monsters culminated to Water Creature. Original video footage captured during the 2017 ArtsIceland residency at the Dynjandi waterfall features characters of water creatures brought to life through costumes, dance, and movement (Figure 20).

Figure 19. Sea monsters research © Public domain.

As archeologist Leszek Gardela and Therry Gunnell observe, folklore constitutes “unofficial knowledge that is passed down between people over the course of time, initially in oral form and in the shape of demonstration rather than through writing.”[1] Because oral folklore is inherently intuitive, much like improvisation, the compositional process relies on spontaneity and immediacy. As folklore evolves through retelling and reinterpretation, performance becomes the medium through which compositional ideas are actualized and communicated in real time. Dutch historian Johan Huizinga refers to this as “‘play’ […] liminal activities which are both temporally and spatially separated from daily life.”[2]

The work of Iceland's pioneering nationalist composer Jón Leifs (1899–1968) provides crucial context for understanding the relationship between Icelandic landscape, history, and musical expression. Leifs drew significant inspiration from ancient Icelandic literature, influenced by its “taut rhythm and crisp accents.”[3] As he noted, the structure of Eddic “verse suggested to Leifs ‘an almost symphonic preparation… a presentiment of majestic, musical motives with their bold, rhythmic rise and fall, their intensification and relaxation.”[4] This illustrates the deep relationship among language, rhythm, and music within Icelandic culture.

Themes of life and death, love, nature, and resilience against hardship permeate Icelandic music. Leifs encapsulated the harsh conditions that characterized early 20th-century Iceland, the same circumstances that propelled many Icelanders like my great-grandparents, to emigrate to Canada in the 1920s. These hardships fueled deeply expressive works that juxtapose stark beauty with raw intensity, creating a uniquely Icelandic musical language reflecting both majestic landscapes and inhabitants' struggle for survival. Much like Iceland's perpetually shifting weather and landscapes, my compositional approach embraces impermanence and transmutation. This comprehensive theoretical foundation establishes the conceptual frameworks that will guide the analysis of individual compositions in the chapters that follow.

[1] Leszek Gardela and Terry Gunnell, “Folklore and Prophecy,” in The Norse Sorceress: Mind, Body, and Magic in the Viking World (Oxbow Books, 2023), 41.

[2] Terry Gunnell, “Spaces, Places, and Liminality: Marking Out and Meeting the Dead and the Supernatural in Old Nordic Landscapes,” 27.

[3] Árni Heimir Ingólfsson, “Leifs and the Elements of an Icelandic Style, Eddas and Sagas,” in Jón Leifs and the Musical Invention of Iceland(Indiana University Press, 2019), 107.

[4] Ibid.

Ethereal Channels of Existence offers a comprehensive investigation into the transformation of inherited sonic and visual archives into contemporary artistic expressions through research-creation. Engaging the cassette recordings of my great-grandmother, Ingibjörg Guðmundsdóttir (1891–1994), not as static historical documents but as collaborative partners, this project demonstrates how performance-based inquiry can reveal forms of knowledge inaccessible through traditional analytical methods.

The central research question, how the creative process itself, through the interaction of ancestral sources, electronic processing, embodied performance, mythological research, and improvisation, generates new works, has been explored through three distinct audiovisual movements: Sleep Darling, La Forêt Invisible, and Les 9 Mondes. Each movement originates from an Icelandic folksong and unfolds into new sonic and conceptual territories through sampling, cello improvisation, and real-time electronic processing with Ableton Live and Resolume.

Chapter 1 explored the braiding of my creative process through the recordings of my great-grandmother, Icelandic folklore, and mysticism. This foundational chapter examined the origins of the project, the role of improvisation and ancestral voice, mythology and symbolism, intuition and transformation, and Icelandic musical influences that shaped the work's conceptual framework. Chapter 2 examined my influences and artistic connections, investigating genre-bending and rule-breaking approaches that inform the project's interdisciplinary methodology. Chapter 3 presented the musical and visual work itself, exploring the reciprocal relationship between sound and video and demonstrating how the three movements function as embodied research outcomes.

Grounded in Robin Nelson's practice-as-research framework and Linda Candy and Ernest Edmonds's processual research-creation models, this methodology validates artistic practice as a legitimate form of scholarly inquiry. It also addresses Terry Gunnell's concern for recontextualizing ancient oral traditions by engaging them through contemporary lived experience. The three artistic residencies in Iceland were crucial in this regard, enabling direct contact with cultural landscapes and local mythologies that shaped the original folksongs.

Through embodied cello improvisation in dialogue with Ingibjörg's recordings, I uncovered musical and emotional resonances that could not be accessed through textual analysis alone. These interactions emphasized how knowledge emerges through doing, through the creative process itself.

Managing live cello performance alongside real-time electronic processing and visual triggering presented a significant cognitive and physical challenge. Yet, these difficulties led to technical innovations: new performance techniques emerged, integrating sound and visuals in ways that neither purely acoustic nor digital methods could achieve alone.

The visual components, developed in Resolume, remain as central conveyors of mythological symbolism, creating dynamic visual metaphors for the narratives embedded in the folksongs. Moreover, process documentation created records which validated intuitive and affective forms of knowledge-making while also providing material for further reflection and refinement.

This research lays a foundation for future exploration of archival activation through interdisciplinary research-creation. It opens possibilities for expanding technical setups for greater fluidity between acoustic and electronic systems, deepening the dialogue between traditional cultural materials and contemporary performance technologies. The three movements, Sleep Darling, La Forêt Invisible, and Les 9 Mondes, function as prototypes for continued exploration. They suggest new ways to combine instrumentation, arrangement, and technological frameworks.

Ultimately, Ethereal Channels of Existence illustrates how research-creation can offer alternative modes of cultural transmission, ones that are embodied, affective, and temporally fluid. By transforming archival traces into immersive and evolving artworks, this project contributes to a growing field of inquiry that reimagines how knowledge, memory, and creative agency flow across generations.

BONUS TRACKS

Dichotomy

Sorcery